Liveweight Recording for Dairy cows

By Bill Montgomerie

New Zealand Animal Evaluation Ltd AE Manager

September 2005

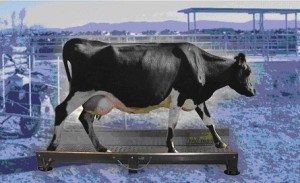

New weight recording technology is becoming very useful for New Zealand dairy farmers. Just as we like to know what is happening to milk production through the season, we like to know what is happening to liveweight. Are the milking cows losing or gaining condition at the rate expected for the stage of lactation and the feed conditions? Are some cows changing weight more than others, indicating some stresses are affecting them? As herds get larger reliable data on body weight is likely to become practically essential for management decisions. And the technology is available to obtain weights as cows leave milking, without disturbing their normal routines.

Use One – Management

If you want this information for management purposes, I would like to remind you that the information is useful for culling and breeding decisions too. For example, very large cows need a lot more feed for annual body maintenance than medium-sized cows. And most herds have quite a large variation in liveweight. For my own herd, every time it has been weighed, the biggest cow has always been at least twice as heavy as the smallest cow.

What does this mean for your culling and breeding decisions?

Use Two – Cull Decisions

Taking a culling example first – let’s say you have a moderate producer that is a large cow, and we will call her Big Bertha. Without any liveweight records for Big Bertha, the calculations for the Production Worth (PW) index proceed on the basis that her expected liveweight is in line with her parent average for liveweight – in just the same way that her expected protein producing ability is in line with parent average before she has been herd tested. Underlying the PW index is an estimated Production Value (PV) for each trait in PW, including liveweight. If Big Bertha does not have a liveweight record, her PV for liveweight defaults to parent average.

However, parent average is not a perfect indicator for Big Bertha’s size for two reasons – one genetic and one non-genetic. Genetically, when the cow was conceived she received her own unique sample of parental genes. In some cases there are major effects on liveweight from the unique sample of genes transmitted to a particular animal, in comparison to the effects predicted from parent average. In our high school biology classes this feature of inheritance was described as “Mendelian Sampling” – and it makes all individuals unique (apart from identical twins and clones). So ancestry information guides us on what to expect on average for offspring of recorded parents, but the biology of reproduction means that there is considerable genetic variation between offspring of the same parents. In fact, the animal breeding textbooks show that the genetic variation among offspring of a single cow and a single bull of the same breed is big – half of the total genetic variation among the entire breed population.

There are also important non-genetic factors that influence how large Big Bertha will be – good or bad luck in exposure to diseases while she was growing, as an example. The impact of these permanent, but non-genetic, factors is similar to the impact of genetic factors in affecting liveweight differences between cows of the same breed and the same age, and calving in the same herd on the same day. For convenience these non-genetic effects are called “Permanent Environment” effects. Permanent Environment effects are just as likely to be negative as positive for any particular animal, and the same is true for Mendelian Sampling effects. Each of the effects averages out to be zero across many animals. Consequently, parent averages give unbiased predictions for the merit of animals that don’t have performance records of their own. But better estimates can be made when records from the cow’s own performance are available, and farmers herd test for just this reason.

What does this discussion of Mendelian Sampling and Permanent Environment effects add up to as far as liveweight recording is concerned? Let’s say Big Bertha’s unique sample of genes was directing her to be 20 kg heavier than expected from parent average, and her own Permanent Environment effects added to another 20 kg. In this case she is really 40 kg heavier, compared to her herdmates, than we can tell based on an estimate from parent average.

So what?

Well, quite a lot really. The annual feed required to maintain an extra 40 kg of liveweight is around three quarters of a big round bale of baleage. If you can trade these bales at around $48, then Big Bertha’s unaccounted extra liveweight is costing you over $30 per year. Put another way – Big Bertha’s PW index has been overstated by about $30. Seeing she is a pretty moderate producer, she might be a cow that should be on your culling list. There is no implication in this that there is anything wrong with having large cows – just be aware that larger herdmates have to out-produce average-sized herdmates in order to earn their keep.

If you have liveweight records for your cows, then it is well worth sending them in to get more accurate indexes for the cows. Studies have shown that more accurate selection decisions justify a cost of $1.75 per cow for getting the liveweight records. Increasingly farmers are finding that liveweight records are very helpful for management purposes. If you are weighing the cows anyway, getting the records into the AE system will help you make better culling and breeding decisions.

Use Three – Breeding Decisions

Now let’s examine a breeding example more carefully. Let’s say you have a high-producing daughter of a bull that tends to leave large daughters. Let’s say that the high-producing daughter in your herd is really a medium-sized cow, but you haven’t sent in liveweights for the AE system as part of your herd performance recording. Then the system only has performance records for sisters, and aunties and nieces and other relatives.

For breeding value estimation the liveweight records of these relatives remain important, even when a cow’s own liveweight has been recorded, because they are part of the overall genetic picture. But in the case we are discussing, the information about the medium size of your particular daughter of this bull is completely missing from the picture.

Now if you send in liveweight records for your herd, and these show that this cow is really only medium-sized. In this case, depending on the number of records, around a quarter of the emphasis in her liveweight breeding value estimation would come from her own records, and her liveweight breeding value would be noticeably more accurately assessed. In typical cases, the Breeding Worth index for a cow like this could be $8 higher – and you are better placed to make good breeding decisions.

Disappointing Trend

by Ian Wickham, September 2005

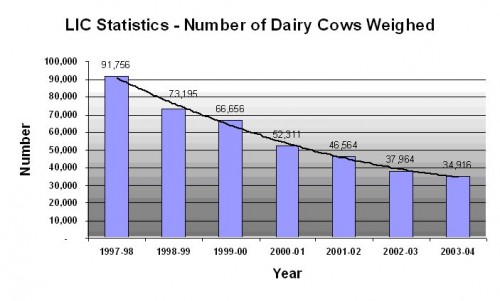

During my research on the topic of weighing dairy cattle, I assembled the data shown in the Chart at the foot of this page titled ‘LIC Statistics – Number of Dairy Cows Weighed’ which demonstrates the abysmal trend of the number of dairy cows weighed in N.Z.

When one realizes that about 25,000 of these cows MUST be weighed as 2 yr old cows for Sire Proving & Progeny Test TOP contracts, and that probably all of the balance are made up of about 10% of those herd owners who weigh the balance of older cows in the same herds – THEN IT APPEARS THAT NO OTHER DAIRY FARMERS ARE RECORDING WEIGHTS, even if they have weighed them.

NZGC has a data base of fully recorded weights on over 200,000 heifers during the past 10 years and NONE OF THOSE HEIFERS HAVE SUBSEQUENTLY BEEN WEIGHED AS COWS IN THEIR HERD.